Fixing classification errors with ClassCorrect

Problem Statement

Businesses often have to deal with categorical data that contain wrongly classified entries. These errors can have an impact on business processes and, ultimately, the bottom line. At Insight, I worked on a project for a firm to implement a code module which detects classification errors and corrects them.

The firm’s product relies on classifications of the data entries, each consisting of a short 5 to 10-word description, to provide meaningful output. The data itself comes from a third party source, and contains about 30 million entries and around 120 pre-set classes. However, a portion of the entries had been put in the wrong classes. Although rare, such errors can have a significant impact on the reliability of the product. To detect such mis- classifications and correct them, I developed a solution dubbed ClassCorrect that predicts the correct classification of an entry based on the description and previous classification.

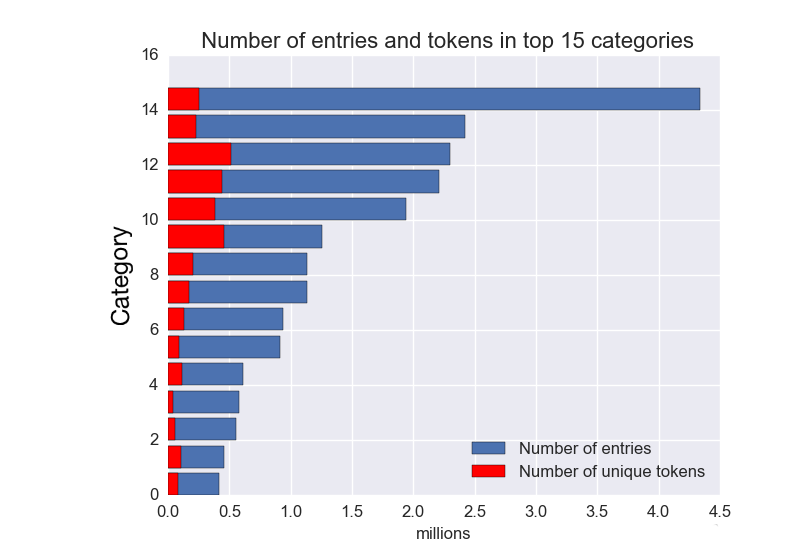

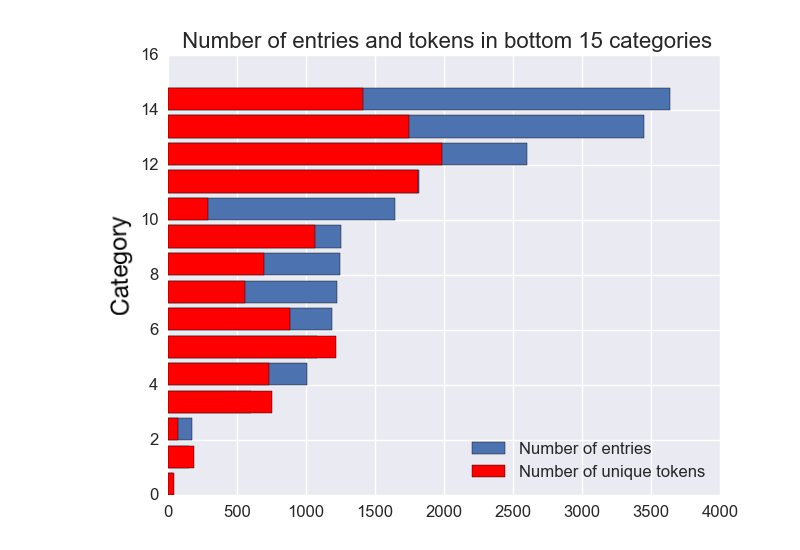

My approach was to use natural language processing with a combination of machine learning models to identify patterns in the descriptions that may accurately predict the right classes. The data itself presented significant challenges. First of all, it is highly imbalanced across a large number of classes. The charts below show the numbers of entries (blue bars) in the top and bottom 15 classes, which can range from over 4 million to less than 1000. A multi-class approach with bootstrap re-sampling might have worked in such a scenario, but for another issue. The red bars in the charts show the number of distinct unigram tokens in each class, obtained by vectorizing the description of each entry using the bag-of-words scheme, where each token represents a feature. While the top 15 classes have nice small token-to-entries ratio, the numbers of tokens in the bottom 15 classes are large compared to the numbers of entries. That means that the multi-class + bootstrap approach is likely to over-fit some of these classes. Furthermore, the proportion of mis-classified entries in each class was unknown, although a brief inspection of randomly selected entries suggested that the majority was correct. Nonetheless, systematic mis-classifications in certain classes may contribute a significant amount of error.

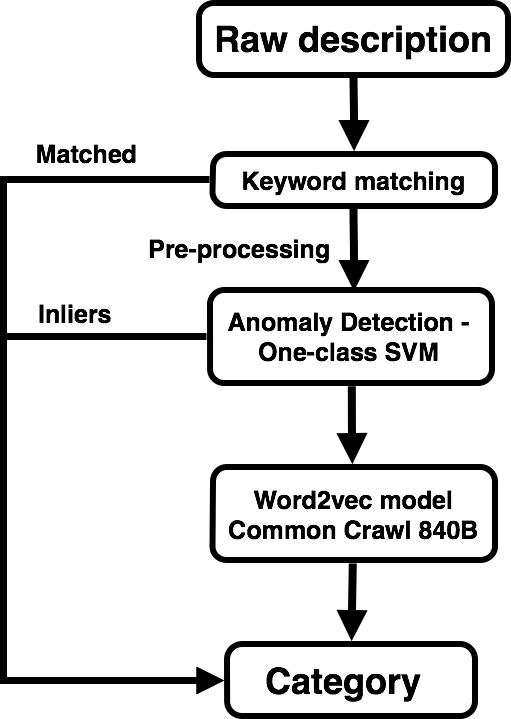

ClassCorrect is divided into two major steps. In the first step, outliers (entries whose descriptions are least like others in their classes) are picked out by a one-class SVM model, which had been trained on the dataset. Outliers are then fed into a second model, which was pre-trained on an external corpus, and a new class is determined. Before each step, a series of pre-processing treatments were applied to the entries. Read on for more details on each of these components. Or you could skip to the next section to learn how well this approach worked.

Solution

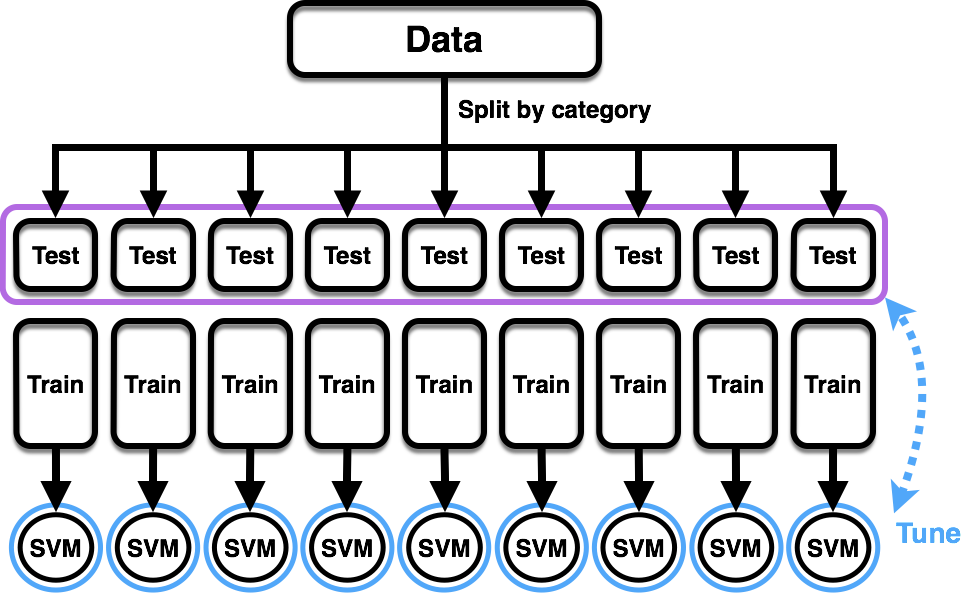

The first step, ClassCorrect.Layer1, performs anomaly detection using One-Class SVM using the NLTK and scikit-learn toolkits for pre-processing and model building respectively. This model assumes that the proportion of incorrect classifications is very small (pedantic point - the formulation actually assumes that all training points are correct classifications). Like a regular SVM, the one-class SVM uses a hypersurface in feature space to define the boundary between two distinct classes. The difference is that in one-class SVM, all the training data belong in one class, and the dividing surface is constructed in such a way as to exclude a user-specified proportion of data points, which are then considered as outliers. To train the SVM models, the dataset was split by class, then again into training and test portions. For each class, a one-class SVM model was trained on the corresponding training set. Each model was also tuned by running predictions on in-class and out-of-class entries from the test set, and maximizing the F1 score over a parameter grid search. It is worth bringing up again the caveat that both the training and tuning procedures assume that the number of misclassifications in the dataset is too small to be significant.

In the next step, ClassCorrect.Layer2, a new class is predicted for each outlier. My first attempt was to use topic modeling via Latent Dirichlet Allocation with tf-idf weighting. However, it turns out that the topics did not correlate with the classes most of the time. Upon an inspection of a subset of the data, it seemed to me that very few classes actually had entries with the same words recurring in their descriptions. These tended to be large classes with common tokens found across multiple classes. For most classess, words that are more indicative of the class occur very infrequently, for various reasons including the use of synonyms, infrequent occurrence of named entities. Thus, an approach that learned semantic relationships between words may have a better chance of success.

To make use of semantic relationships in the prediction, I chose a text embedding model. I was not able to find a corpus specific to the context of the documents I was dealing with, so I decided on an all-purpose corpus. Common Crawl, which trawls the internet and compiles web content into a humongous corpus, is as general a corpus as one can find. The corpus contains 840 billion documents and would be a real pain to train. Fortunately, a pre-trained GloVe model exists. In my implementation, I converted the model to the Word2vec format. The principle behind such models is text embedding, in which a 2-layer neural net is fed documents from the corpus and subsequently assigns each word to a point in some high-dimensional space. The semantic similarity between two words in this space can be gauged by the cosine similarity between the two representative points. This allows semantic operations such as the classic “king - queen + woman = man”. With this useful tool, I can average the similarities between words in the entry description and words in the class name, and assign to the entry the class that gives the highest similarity score. But wait, what about words that occur commonly and are similar to many classes? In the spirit of tf-idf, I weighted each token with the logarithm of the ratio of the number of classes to the number of classes that have positive similarity between their names and the token. Another problem is that class names can be quite ambiguous, leading to weak semantic similarities with all descriptions. Against this problem, I adopted two measures, the first of which was to manually replace ambiguous class names with more specific descriptions, or with specific examples. The second measure is an automated means of doing essentially the same thing as the first measure. Word2vec models are able to produce a collection of words that are most similar to a given set of words. With this functionality, I was able to expand each class name into a larger set of related words.

The input to ClassCorrect is the entry description. Pre-processing included the removal of stopwords, as well as words that were less than two characters long or words that occurred less than 4 times in the entire dataset. After that, the remaining words are run through a spellchecker. pyEnchant is a pretty good spellchecker which gives multiple suggestions. Each word is checked for existence in the Common Crawl corpus. If it does not exist in the corpus, then the spellchecker is run on the word and subsequently a list of possible replacements is generated. In ClassCorrect.Layer2, when the entry is compared to each of the classes, the replacement word with the highest similarity score to the class is selected during comparison to that class. In other words, the choice of replacement word depends on which class the entry is being compared to. This methodology allows ambiguity between replacement words to be resolved.

Performance

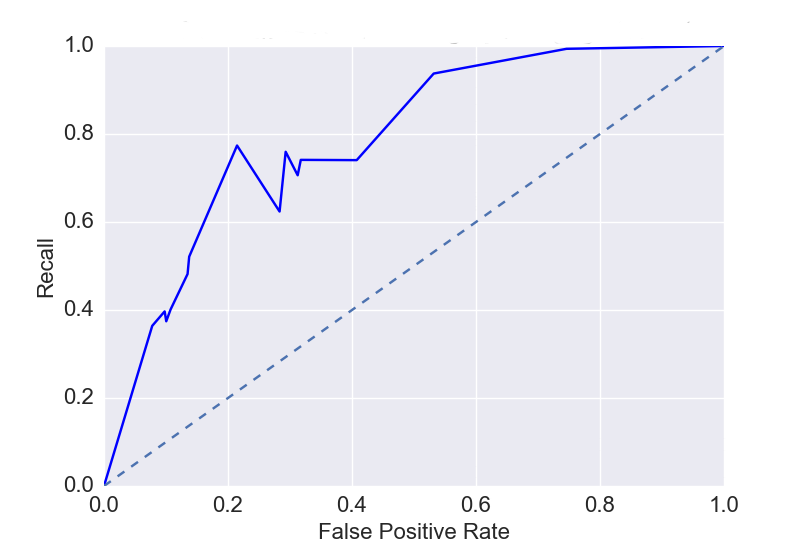

For the anomaly detection step, a one-class SVM model was trained for each class, using all but 1000 entries which were used for testing. A gridsearch was performed over the nu and gamma parameters. A sigmoid kernel was used because it performed better than linear, polynomial, and radial basis function kernels in preliminary tests. Shown below is an optimal (highest AUC over gamma parameter) ROC curve for a typical class. Optimal parameters were then selected near the inflection point, giving a precision and recall of 0.78 and 0.77 respectively.

In the current implementation of ClassCorrect.Layer2, the model used is a pre-trained one and not tunable. I tested the model using both equally weighted tokens, as well as tokens weighted by a tf-idf-like scheme, where the similarity to a given class was multiplied by the logarithm of the number of classes to the number of classes for which the similarity was positive. The latter weighting scheme produced a marginally better accuracy of 25% (proportion of test data matched to the correct classes) when tested on 30 previously mis-classified entries (these were rare and had to be hand-picked). The low accuracy was not altogether unexpected. For many previously mis-classified entries, the description did not contain words that were semantically similar to the class descriptions. Instead, a better approach might be to perform a named entity lookup to match entities to possible classes. To this end, I built into the code a mechanism to allow manual input of keywords which would trigger immediate matching to a specified class or restrict class comparisons to a small subset when found in a entry description.

Finally, the entire pipeline, consisting of keyword search, anomaly detection, and finally new class assignment, had an accuracy of 80% when tested on the same test set used for SVM model tuning. By keeping most of the correctly classified entries and correcting a portion of the mis-classified ones, the overall performance of ClassCorrect is an improvement over what the firm had previously. There is potential for further improvement as the firm injects domain expertise into the model through the keyword mechanisms I had implemented, and possibly by using a different text embedding model with either a corpus more specific to the context of the descriptions or with the inclusion of bigrams to capture two-word entity names. Another avenue for improvement is re-definition of classes, to either dis-ambiguate overly inclusive classes or merge closely related classes.